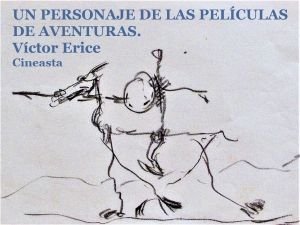

A character from adventure films. Víctor Erice (2005)

Text included in the book “El hacedor de sueños”, published on the occasion of the exhibitions in homage to Enrique Gran.

Caja Cantabria Cultural Centre, Santander, 2005.

Caja Cantabria Palace, Santillana del Mar, Cantabria, 2005.

Centre of Lebaniego Studies (Church of San Vicente), Potes, Cantabria, 2005.

A CHARACTER FROM THE ADVENTURE FILMS

I met Enrique Gran in the autumn of 1990, a few days after he began to produce El sol del membrillo in Madrid. Enrique had just returned from one of his trips to Santander and, with the help of Antonio López, he joined the shoot one morning, with admirable spontaneity and dedication. His physical appearance was in keeping with his surname. When I saw him for the first time, striding down the Calle Poniente – a leather shoulder bag, dressed in an explorer’s shirt and jeans, his head covered with a visor cap that gave him an air of a sailor on land – I immediately had the impression that I was in front of a character from one of those adventure films that made my childhood so happy. So I don’t think I’m exaggerating if I say that never has a painter who has been at work in front of the implacable eye of a film camera had a better travelling companion.

In fact, his presence in the film soon proved to be very important, especially in the remembrance that he and Antonio López made of certain years of their youth, those of the birth of their friendship at the beginning of the 1950s, both being students at the School of Fine Arts in Madrid. Enrique’s memory of that period was generally marked by melancholy, in the face of the possible paralysing effects of which he was accustomed to react by invoking the pending task, as if he were aware of the fleeting nature of time. A disturbing melancholy, yes, but also a creative one, which, as far as El sol del membrillo is concerned, crystallised in his moving evocation of a photograph taken by Conchita, a fellow student, for whom he and Antonio López had posed at the door of the Escuela de San Fernando. His desire to recover that lost image so as to be able to show it to Antonio – and to the spectators as well – led him to undertake the search for its author, whom he only knew to reside far from Madrid, in an imprecise place on the Levante coast.

Multiplying his investigations as the filming progressed, when he was finally able to find her whereabouts, he discovered that Conchita, affected by a serious illness, had died a few days before, just when he, in front of the camera, remembered her again and again. Out of respect for her pain, I did not want to include this sad ending in the film. In the film story the search for the photo remained unresolved: the viewer was never able to see the image. All that remains of it is its reflection, the testimony of Enrique evoking it for Antonio: – “It was a very beautiful photo. We were both at the door of the School. And facing us, Conchita took the picture.

I was very impressed because the gesture of both of us was the same, that is to say, the passion for art and the slab that we carried on our backs when we were broke? It is clear that in Enrique’s memory Conchita’s photography was endowed with an aura that drew in the expression of Antonio López’s faces and he the original trace of his vocation. Or what is the same: the unequivocal sign of a form of destiny capable of overcoming all the tests of reality, and which projected a figure of romantic lineage, that of the hero painter. An exemplary figure with novel features – which Nieva has opportunely highlighted in a recent and magnificent article1 – to which Enrique Gran was always faithful in more than one aspect. The – tragic – end of his life confirms this sign of his character: locked up in his Madrid flat, outside the world, painting and painting without stopping.

I myself was able to verify this every time I visited him in those last years. Captivated by an inner vision, his paintings grew around him at a dizzying rate, piling up everywhere. In that place there was only room for painting; everything else had been left out. Embarking on a process of radical self-absorption, sheltered in a silence – “delirious and silent, like his painting”, wrote Nieva – which was difficult to break, the artist had set off without looking back, determined to fulfil the destiny he himself, in a unique and youthful gesture, had outlined in the air one day: to live and die painting.

Victor Erice. Film director

Madrid, 8 January 2005